Loading paired reads from position-sorted BAM files

BAM files with sequence alignments sorted by genomic position seem to be the new currency of exchange for large-scale human genome sequencing projects. This is convenient and practical in many ways for many people. But in my current research I work a lot with tools that only want/need the sequence information and, for whatever reasons, support only FASTA or FASTQ input.

A quick Google search will identify several freely available tools for extracting read sequences and base qualities from a BAM file and writing them out in FASTQ format. I have used several of these tools during the last couple of years. The catch is that if one wants to retain pairing information, all of these tools require the reads in the BAM file to be sorted by read name. BAMs are more commonly sorted by genomic position—this is certainly the case for all the data sets I've work with—and for BAMs occupying more than 100G of storage space each, re-sorting requires a non-trivial amount of compute and disk I/O.

Today as I was waiting yet again for a samtools sort -n job to finish, I gave this problem some thought.

When read alignments in a BAM file are sorted by genomic position, we should expect paired reads to occur in close proximity.

If this expectation holds true, then position-sorted BAM files lend themselves to a fairly simple and efficient strategy for conversion to paired FASTQ format—or more generally, to loading read pairs—without the need for sorting by read name.

The experiment

To assess my intuition, I hastily threw together a little experiment, implemented as the following Python program. In brief, it:

- iterates over read alignments in the specified inpyt BAM file

- skips the first million entries (this is probably unnecessary, but it's a habit from working with FASTQ files which often have a bunch of junk reads at the beginning of the file)

- stores the next 10,000 entries in a hashtable (a dictionary, for you Python folks)

- continues iterating over the entries in the BAM file; if the current read is paired with a read already stored in the hashtable, the program calculates the number of entries separating the pair and prints this out

#!/usr/bin/env python

import argparse

import pysam

import sys

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument('--out', type=argparse.FileType('w'))

parser.add_argument('bam')

args = parser.parse_args()

reads = dict()

bam = pysam.AlignmentFile(args.bam)

storedreads = 0

pairsfound = 0

for i, record in enumerate(bam):

if i < 1000000:

continue

readname = record.query_name

if storedreads < 10000 and readname not in reads:

reads[readname] = (i, record)

storedreads += 1

continue

if readname in reads:

other_i, other_record = reads[readname]

dist = i - other_i

print(readname, other_i, i, dist, sep='\t', file=args.out)

del(reads[readname])

pairsfound += 1

if storedreads == 10000 and len(reads) == 0:

break

print('processed', i, 'reads', file=sys.stderr)

for readname, (i, record) in reads.items():

print(readname, i, '-', 'inf', sep='\t', file=args.out)

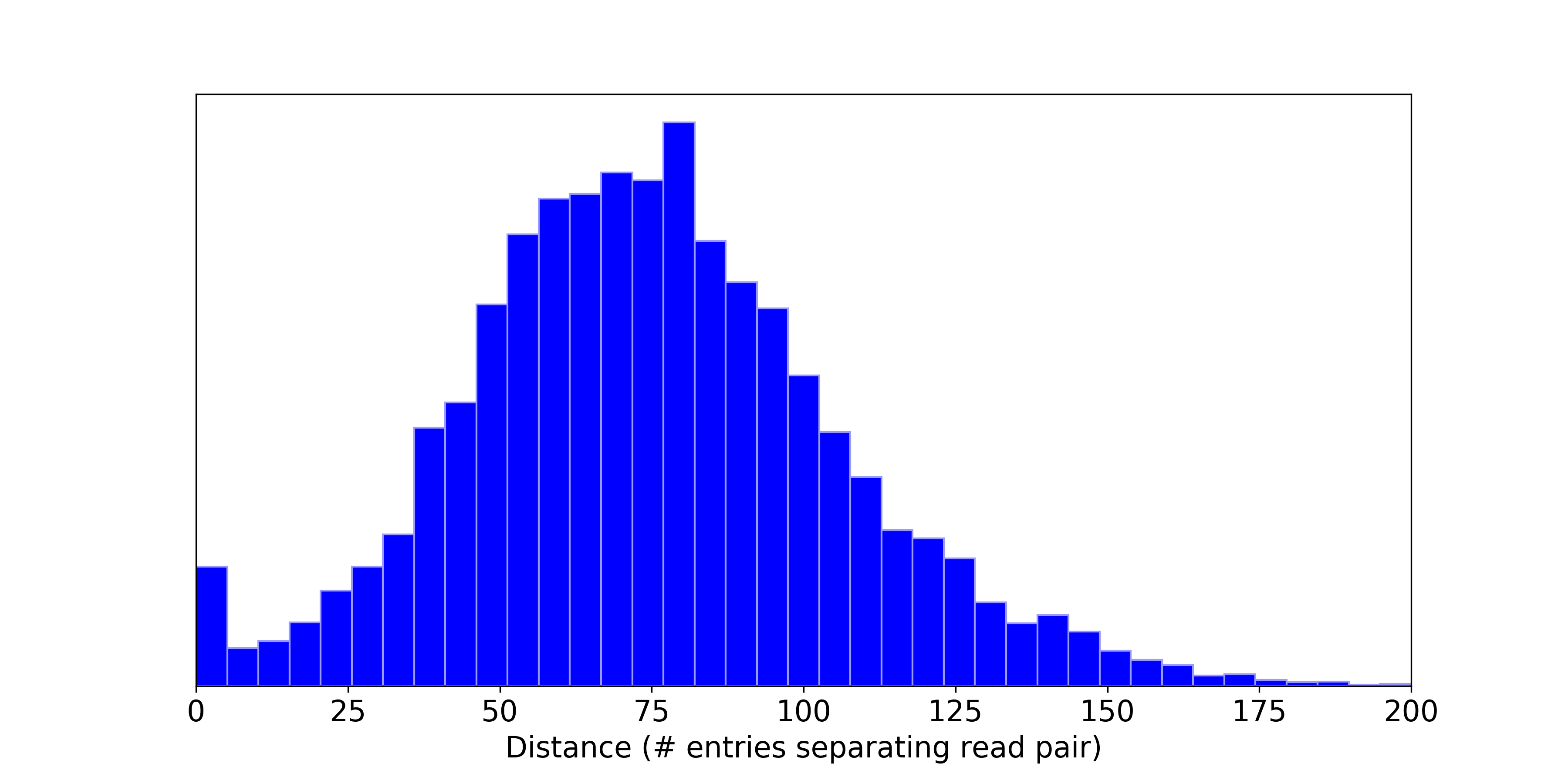

So in the end, this gives a distribution of "distances" between paired-end read alignments in the BAM file, with distance measured as the number of other reads separating the pair.

I ran this experiment on a BAM file with nearly 1 billion reads and got the following results.

Out of the 10,000 arbitrarily selected reads, 60 mysteriously had no pair anywhere in the entire file. For another 27, the pair was separated by tens or hundreds of millions of entries, presumably due to a misalignment, and unmapped read, or one of the pairs aligning to an alternate or decoy sequence that sorts to the end of the BAM file. But for the remaining 99.13% of the reads, pairs were separated only by dozens of entries.

The strategy

Based on this observation, my proposed strategy is to load BAM entries into memory while iterating through the file. Assuming the trend observed in my experiment holds throughout the entire file, we can be assured that most BAM entries will not remain in memory long. Once their paired read has been found (usually within a few dozen entries), both reads can be sent to the output and removed from memory. If there are any entries left in memory after traversing the entire BAM file, these mateless reads can be output as singletons.

So just how much memory do we expect this to require? Let's consider the data set we examined above with about 991 million reads, and let's assume 0.87% of the reads will need to be kept in memory for most or all of the program's runtime. This amounts to about 8.5 million reads. In Python, storing this many BAM entries in a Python dictionary required about 9 GB or memory. This is feasible on many laptops and desktops these days, and is peanuts for the systems running most genomics workflows. Plus, if this strategy were implemented in C++ or some other language with less overhead than Python, we could expect the memory usage to be even less.

The implementation

I don't have the attention to implement a high-performance solution for this in C/C++ at the moment, but I'd like to get something down while this is all still fresh in my head. Throwing together something in Python with the pysam module should be pretty straightforward, so watch this space for updates!